Common Knowledge, the Symbolic, and the Imaginary

February 4, 2021

It seems Squarespace have upped their cynical advertising game, perhaps surpassing last year’s A Website Makes it Real campaign with a new Super Bowl commercial that overlays a reworked version of Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5 on a horrorshow romanticisation of boundless productivity and eternal work (sorry. . . side-hustle).

What’s striking about this advert is not so much the bleak messaging as its self-awareness. It is deliberately cynical, and this makes criticising the message feel utterly pointless. Critique, it might be argued, brings agency only if it pierces an illusion to reveal a hidden truth. But Squarespace is not trying to create the illusion that something bleak is empowering. This advert does not pretend—it pretends to pretend. To earnestly dissect the content as distorting a bleak reality would be to treat it as a straightforward pretence—but to do this is just to become complicit in the 2nd-order pretence. What’s the point?

This pattern of reception, interpretation, self-reflexive cynicism and apathy is fairly representative of the sense of powerlessness that modern marketing is uniquely effective at producing. The situation is similar to what Mark Fisher called reflexive impotence:

It is reflexive impotence that you hear in the Arctic Monkeys - yes, they know things are bad, but more than that, they know they can’t do anything about it. But that ‘knowledge’, that reflexivity, is not a passive observation of an already existing state of affairs. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. And guess what? They probably know that too.

Not only does knowledge of the bleak reality fail to help overcome the impotence, it actually helps to create it. But how? What is the mechanism?

In the case of advertising, it is common to appeal to virality. Squarespace doesn’t really care if you actually like their message or not, they just want you to share it. Their strategic aim is simply to maximise polarisation. Pro-side-hustle people can rave about it; people like me can rant about it. Everyone is happy—Squarespace get their ad shared widely, pro-side-hustlers feel vilified in their side-hustling, and people like me have yet another thing to pull to shreds, which is ideal because that was our content model anyway. Cheers Squarespace!

But this still doesn’t make any sense. The final measure of success of an advertising campaign is whether it drives consumer behaviours, i.e. gets more people to actually buy the thing it’s selling. Wide sharing may be instrumental to this end, but it is not at all clear how negative visibility can drive consumption. Hating something might get a lot of people talking about it, but why would it make them buy it?

Common Knowledge

In his book Rational Ritual, Michael Chwe makes some suggestive connections between these puzzles and the notion of “common knowledge.” (Chwe, 2001) A group is said to have common knowledge of something if they all know it, they all know that they all know it, they all know that they all know that they all know it, and so on.

Common knowledge is important for solving coordination problems—situations where the decisions of individuals are dependent on the decisions of many other people. Say you are considering buying one of the first fax machines. You are very much up for putting your money into this new futuristic gizmo, but it is pointless to do so unless many other people feel the same way (you don’t want to end up faxing yourself). It may be that there are many people also prepared to get on board, but if you don’t know this then you can’t be confident that you’re not wasting your money. What is missing here is common knowledge: if everyone knew that there are many others who want one (and knew that they knew, etc) this would give everyone the confidence to go ahead and get one.

This is where advertising comes in. Chwe’s argument is that events with huge audiences—like the Super Bowl—have such high value to advertisers not so much because they allow them to get their message to large numbers of people, but because the receivers of the message will be aware that many other people are also receiving it. They are valuable because as massively public focal points they can be leveraged to create common knowledge.

Many have argued that advertising “creates needs” that people would not have cared about otherwise […]. But perhaps it is less a matter of creating individual isolated needs than of tapping into the deep and basic need of each individual to conform to community standards, an ever present coordination problem. (Chwe, 2001, p. 41)

This kind of thought applies to social goods—goods which people want because other people want or have them (for whatever reason). In such cases, Chwe’s argument suggests that publicity itself is much more important than content.

Take this Apple commercial from the 1984 Super Bowl:

It’s all very well to watch this as a youtube video embedded in some obscure blog post, but to see it at the Super Bowl is different, in a straightforwardly objective way—you know that millions of others are also seeing it at the same moment. This makes a rational difference to the choices you might make. This gives some concrete shape to McLuhan’s idea that the medium is the message. This has nothing to do with some mysterious pull that the medium exerts over the content of its messages but because formal qualities—like publicity—affect their objective significance for social reasoning.

This would explain why it doesn’t really matter if individuals are directly responsive to the messaging in adverts. Their success is not based on whether they are persuasive at an individual level, but on whether they establish a point of shared reference within the space of common knowledge, because this is the significant factor for decision coordination.

The Symbolic

Towards the end of the book, Chwe warns that content and publicity are not quite as distinct as this argument suggests, and can interact in peculiar ways. This is because a public transmission always has an implied audience, and must therefore assume a shared symbolic vocabulary.

The point here is that common knowledge depends crucially on how each person understands or interprets how other people understand or interpret a communication. (Chwe, 2001, p. 83)

Squarespace stand at something of an interesting position within this tangle, since the product they are selling is effectively the means of common knowledge production. They are trying to sell you a way of making your thing a public thing, in some suitably qualified sense of “public.” A website makes it real, remember? If Chwe’s argument is barking up the right tree, then the success of the Squarespace advert should depend on its generation of common knowledge about common knowledge production.

And producing common knowledge is different to receiving it. To be part of a group that has common knowledge depends on inhabiting a shared symbolic system—this requires only an implicit grasp of shared symbols and meanings, a kind of communicative know-how which one may not be consciously aware of. But to produce common knowledge requires an explicit grasp of the symbolic system, since this is what must be harnessed and manipulated.

Say you are the kind of person who needs a website—an artist perhaps. You probably do not believe that all meaning in life is derived from work, or that it is possible to side-hustle yourself all the way to enlightenment. Your need for a website more likely derives from a compromise between multiple practical considerations—you want to spend as much of your time as possible doing what you love, don’t particularly want to live a life of either corporate drudgery or abject poverty, are not super enthusiastic about self-promotion but recognise that it’s a necessary evil in a digital obsessed media climate which, let’s face it, you have zero control over.

So you need to play the game a bit, because that’s the least bad option. Playing this game is a question of packaging your work in a public-facing way that speaks in the language of the shared symbolic system—this is what will allow it to participate in the space of common knowledge (i.e. to become real). What you are looking for in a website provider is, ultimately, something which can do as much of this work for you as possible, so that you’ll have more time to spend doing the stuff you actually like.

This is where Squarespace come in. Because packaging your content in a way that speaks this language is not about being the kind of person who believes in the spiritual power of the side-hustle, it is about appearing to be the kind of person who does. Squarespace is selling you the means of appearing to care about side-hustling, and this is why common knowledge is operating at an extra level of removal in this case. What is important is not that the advert convinces you that side-hustling is virtuous, or even convinces you that other people believe it is virtuous, but that it convince you that this is the common symbolic vocabulary that everyone is using to convey self-realisation, even if no-one believes it.

Its success depends on its ability to coordinate our pretences. The horrible irony is that the better equipped you are to see the bleak reality behind the messaging, the more likely it is to achieve this effect.

The Imaginary

Another way of making this point is that rather than generating common knowledge by using a shared symbolic vocabulary, Squarespace are intervening directly in the vocabulary. This is a bit like creating common knowledge ex nihilo, i.e. in a way that moves directly to creating the sense that everyone knows that everyone knows that X, etc., without depending on the base layer: that everyone privately knew X in the first place.

Here is David Lewis, cited by Chwe:

If yesterday I told you a story about people who got separated in the subway and happened to meet again at Charles Street, and today we get separated in the same way, we might independently decide to go and wait at Charles Street. It makes no difference whether the story I told you was true, or whether you thought it was, or whether I thought it was, or even whether I claimed it was. A fictive precedent would be as effective as an actual one. (Chwe, 2001, pp. 79-80)

This example shows the use of common knowledge to coordinate action doesn’t necessarily depend on there being a base-layer of truth.

Some friends of mine have a VR set with a trippy meditation app. Everyone is adamant that it is “just like DMT,” even though it is nothing like it. There are some superficial similarities in its vague kaleidoscopic visual effects, but these feel more like a quotation of a psychedelic experience than a serious attempt to simulate one. All of the distinctive characteristics of DMT experiences—radical auditory distortion, loss of bodily awareness, fear—are of course completely absent.

But still everyone insists on the comparison. This is a hype phenomenon that feels very familiar to me, and surrounds VR in particular. It is as if there is some massive collective investment in VR being some kind of breakthrough which will open up new vistas of experience, when in truth a lot of the time it’s just like having a screen that goes all the way round plus a few gimmicks. Of course, talk to any one person on their own and they’ll often be more cynical. But this is always true of hype, which is never about influencing perceptions so much as influencing common perceptions—our perceptions of one anothers perceptions.

While the VR app is in no way a substitute for a DMT experience, it does have something that DMT does not: the experience is shared, in the sense that everybody experiences the same thing. It has a dimension of common knowledge that can never be present for DMT trips. DMT trips are both awe inspiring and private, things you go through alone and then might struggle to convey to other people in terms they understand. This can be weird, disorienting, and hard work.

Hypothesis: the hype behind VR, rather than being due to its capacity to provide us with profound experiences, derives from its ability to bypass a certian kind of social labour, namely that of articulating the personal and profound. To cash in on this we have to keep up the pretence that it really is profound, but this no longer matters. What matters is just that we’d prefer to share a shallow illusion than face a deep reality alone.

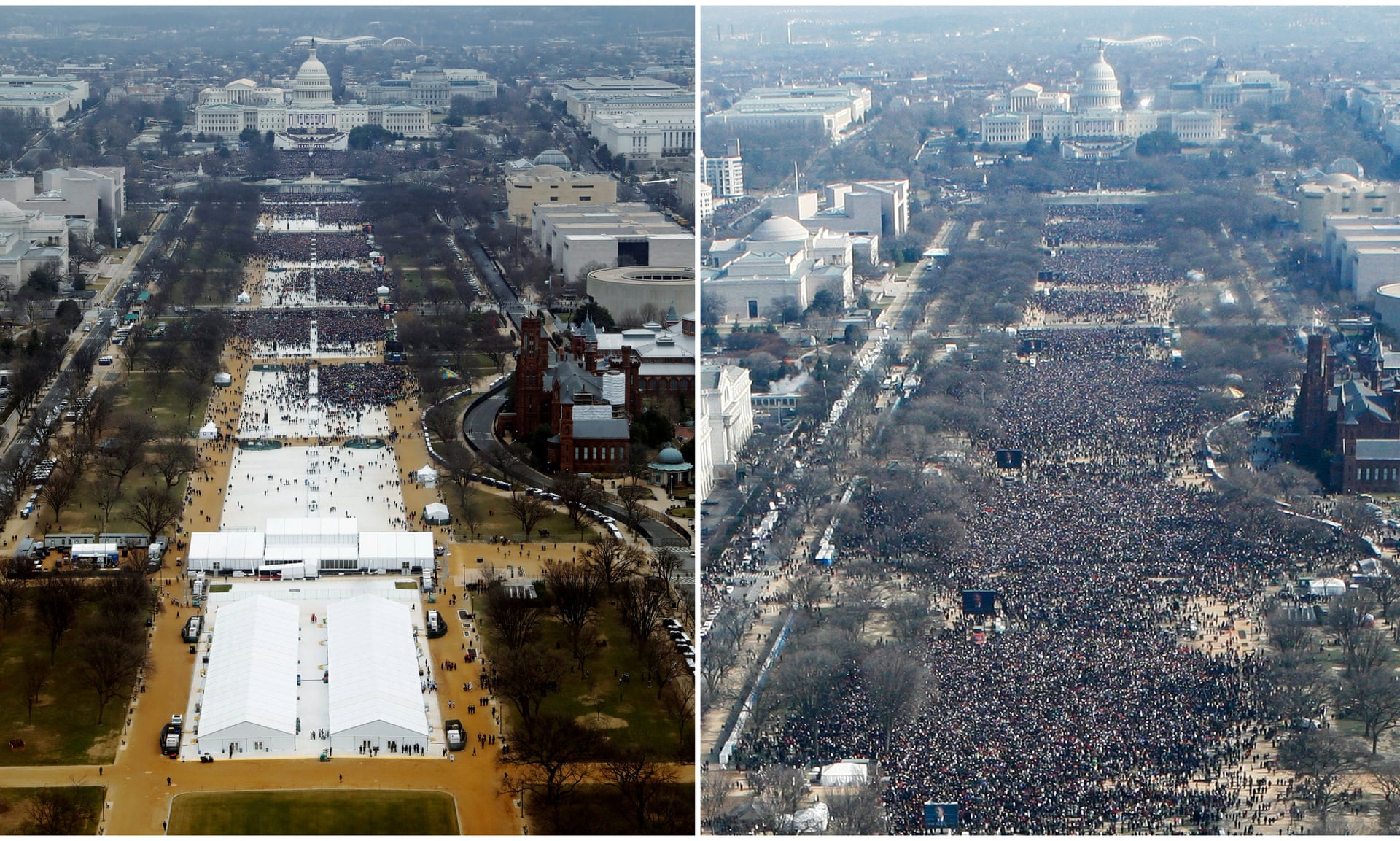

Here is the photo from the Trump inauguration, with Obama’s next to it on the right:

In hindsight, Trump’s response to the evidence that his inauguration was ill-attended was a landmark moment in the post-truth saga. What was significant was Trump’s flat-out denial of the veracity of the image, when there were many other options available to him.

He could, for example, have just said that it was relatively ill-attended compared to Obama’s because Washington DC and surrounding areas are packed to the gills with Democrats. I have no idea whether that’s true or not, or whether other Republican presidents have had better attended inaugurations, but none of that matters—Trump wouldn’t have needed to persuade anyone, only to achieve a baseline level of plausible contestability. After all he didn’t need to persuade his supporters, since they all viewed the media fanfare surrounding this image as a cheap shot anyway, and his detractors were going to ridicule him whatever. The only thing at issue was reputation management in public space, and this was just a question of playing an easy move in a standardised game—making a barely plausible justification would have been fine.

But he didn’t do that—he questioned the veracity of the image directly, calling it fake news. This shares some affinity with the Squarespace strategy: rather than use the symbolic standard to generate common knowledge, it intervenes at the level of the symbolic vocabulary itself. This was only possible against a background suspicion about images that could only exist in the photoshop era (or perhaps all it required was the widespread belief that other people are suspicious of images?). Of course there’s ways of telling whether an image has been doctored or not, but again that doesn’t matter—what is important is that uncertainty over the status of images has become part of the shared symbolic milieu, whether anyone believes that a particular image has been doctored or not. (A great art project that illustrates this point is #HYPERREALCG.)

These are imaginary effects with real consequences. They are possible because common knowledge is causally significant, and it is causally significant because it is critical for coordinating action. By manipulating the imaginary—which is not some dark repository in the spine but is, I think, better thought of as something that lives dynamically in our perceptions of each other’s perceptions—actors can directly influence the perfectly rational decision-making process of individuals. This depends on no illusions, no masks or false consciousness.

Baudrillard:

One both believes and doesn’t. One does not ask oneself, “I know very well, but still.” A sort of inverse simulation in the masses, in each one of us, corresponds to this simulation of meaning and of communication in which this system encloses us. To this tautology of the system the masses respond with ambivalence, to deterrence they respond with disaffection, or with an always enigmatic belief. Myth exists, but one must guard against thinking that people believe in it: this is the trap of critical thinking that can only be exercised if it presupposes the naïveté and stupidity of the masses. (Baudrillard, 1994, p. 81)

References

- Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation (S. F. Glaser, Tran.). University of Michigan Press.

- Chwe, M. (2001). Rational Ritual: Culture, Coordination, and Common Knowledge. Princeton University Press.